- Home

- Denise Scott

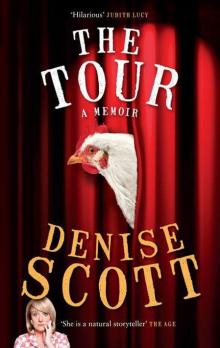

The Tour

The Tour Read online

Published in 2012 by Hardie Grant Books

Hardie Grant Books (Australia)

Ground Floor, Building 1

658 Church Street

Richmond, Victoria 3121

www.hardiegrant.com.au

Hardie Grant Books (UK)

Dudley House, North Suite

34–35 Southampton Street

London WCZE 7HF

www.hardiegrant.co.uk

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publishers and copyright holders.

Copyright © Denise Scott

Cataloguing-in-Publication data is available from the National Library of Australia.

The Tour

eISBN 978 1 74273 844 4

Cover design by Josh Durham/Design by Committee

Text design by Vivien Valk

For May, Marg, Noreen and Julie

Contents

Title page

Copyright page

Prologue: The awakening

1: Beginnings

2: Dreaming big

3: Adolescence

4: Kitchen sink surprise

5: Leaving the nest

6: Teddywaddy dreaming

7: Upping the ante

8: Upping the ante a little bit more

9: Passing the baton

10: The call of the wild

11: Post-awakening

12: Success is …

13: Rash behaviour

14: Chook meet

15: Comedy and death

Acknowledgements

Author’s note

Prologue

The awakening

It was the year 2009 and I was fifty-four years old and it was the night before I was due to go away on a tour and I drank too much.

When I say I drank too much, allow me to be specific. I shared a bottle of wine with my partner, John, but then suspecting he might have had a bit more than me I went to open a second bottle so I could pour myself another glass.

Just as I reached for the second bottle, however, John said, ‘Hang on, Scotty, do you have to open that one?’

Was the man insane?

‘It’s just that it’s a really good bottle, and I was hoping to cellar it for a few years.’

What a wanker! Life’s too short to wait for wine to age. Besides, we don’t have a cellar.

(Here I must apologise to those who read my previous book, All That Happened at Number 26, not for the book—God knows, I did my best—but because I need to repeat a story. But I promise to make it as brief as possible. Then again, if you’re anything like me you’ll have no memory of it anyway.)

When I was four years old I was standing in my Nanna Scott’s kitchen and she said, ‘What do you want on your sandwich, Denise, Vegemite or peanut butter?’ And then she dropped dead. Just like that. There she was, standing at the kitchen table as large as life one minute, and then, bingittybang, dead on the floor the next.

Well, I wasn’t expecting it. And I’m pretty sure Nanna wasn’t. A massive heart attack. She was fifty-nine years old.

I never had time to tell her, ‘Vegemite, Nanna, Vegemite.’

My father met the exact same fate: fatal heart attack at fifty-nine. And since I’m now well into my fifties … You don’t have to be Einstein to join the dots.

That was why, when John told me not to open that second bottle of wine, I responded, ‘John, you know there’s a history of people suddenly dropping dead in my family. That could be me tonight—standing talking to you one minute and then dead on the floor the next—and who would you drink your fancy bottle of wine with then? Your new floozy? The one you meet at my funeral?’

What could he say?

Triumphantly, I opened the bottle and poured myself a glass, or rather a goblet, or more precisely a small fish bowl—this probably best describes ‘Mummy’s bucket’, as we like to call it at our house.

When I was almost finished John stood up and announced, ‘I’m going to bed.’

‘Oh, John, you don’t want to have just one more tiny snifter of wine?’

‘No. And I don’t think you should either, Scotty. Remember what happened last year?’

Tragically, I did remember. And it wasn’t pretty.

I was on another tour at the time, had drunk too much the night before and on the morning in question had to fly in a small plane. It was a bit turbulent, and when we landed one of the young boy comics asked if he could carry something for me. I said thank you and handed him my plastic bag of vomit, which I don’t think he was expecting.

John put the cork back in the wine bottle, assuring me he was doing it for my own good. He put the bottle on the kitchen bench and both wine glasses into the dishwasher. He then headed to the bathroom.

I waited until I heard the sound of his electric toothbrush then got a clean wine glass out of the cupboard and, just in case John suddenly stopped cleaning his teeth, turned the tap on full bore to cover the glug-glug-glugging sound as I quickly poured myself some more wine. Only a quarter of a glass. Or maybe it was a half. Possibly it was verging on three-quarters. Whatever, let’s not get bogged down in dreary details.

The reason I drank so much that night was that I was scared. And depressed. As I said to John later that night as we lay in bed, ‘I don’t want to go.’

‘Why not?’

‘I’m too old.’

‘You are not.’

‘I am, John. I’m too old to be going on a Comedy Festival Roadshow. Do you realise I’m older than all the other comedians’ mothers?’

‘Bullshit.’

‘It’s true.’

‘What about Jeff Green? He’s in his forties, isn’t he? You can’t be older than his mother.’

‘I could. She could have had him when she was twelve. These things happen. Anyway, I’m not funny. At least, I’m not funny enough. They didn’t even laugh at my finger-up-the-arse routine last night.’

‘Scotty, it was a prostate cancer fundraiser. They were a bit sensitive, that’s all. And they did laugh; you just couldn’t hear them.’

‘Why wouldn’t I hear an audience laughing, John?’

‘I don’t know. It could have been the ceiling. You know, it was very high, and all the sound was probably getting sucked up into the roof before it reached you on the stage.’

The old sound-getting-sucked-up-into-the-ceiling routine. John might as well have got a knife, stuck it in my heart and slowly twisted it.

‘Oh John …’ I moaned, indicating extreme emotional pain, ‘of all the places we could go we’re touring to Far North Queensland.’

John said nothing. It was almost as though he didn’t understand the significance of this statement. I had to up the ante.

‘Far North fucking Queensland, John!’

It worked. John responded, although I noted he sounded tired. ‘The problem being?’

‘The problem being I’m fat.’

‘You’re not that fat, Scotty.’

‘What do you mean, not that fat? Fat is fat, John, and I’m fat. I mean, I wouldn’t care if we were going to Tasmania …’

‘What, do you think Tasmanians are more accepting of fat people or something?’

‘No, John. I mean, if I was going to Tassie I wouldn’t have to wear bathers. But Far North Queensland … Oh God, I should have had waxing done. You know how hairy I get. Jesus, these days I have to have a bikini wax not so I can wear bathers, but so I can wear knee-length shorts. And how am I going to explain why I have to wear a scarf in the tropics?’

‘Why do you have to wear a scarf in the tropics?’

‘Because, in c

ase you haven’t noticed, my neck is covered in goobies and skin tags and warts. And what am I going to do when the arthritis in my ankle gets so bad it seizes up and I can’t walk and I just have to drag my leg along behind me? You won’t be there to massage it, John. I mean, I can’t ask one of the young boy comics, “Could you please rub my fat old lady’s ankle?” And what about when we’re all driving around in the mini-van together? What will I talk to those young boys about? Menopause? My dry vagina?’

‘Well, gee, Scotty, if anything’s going to get a young man to look up from his iPhone …’

* * *

I woke with a start. My mouth was dry. I picked up the orange Tupperware cup that sat on my bedside table and took a sip of water. I marvelled at its refreshing coolness. We were so lucky to live in Melbourne—such lovely water, so clear, so clean … Oh, Jesus, my head hurt. I groaned. Why had I drunk so much?

I hung over the side of the bed. Ouch. Upside down, my head thumped even more. I picked up the radio alarm clock and turned it to face me. The bright-green numerals informed me it was 2.06 am. This meant I had slept for approximately two hours. That was, more than likely, all the sleep I was going to get, because not only was I a hormonal woman in my fifties who had drunk too much but I was also a chronic insomniac.

I got up and went to the toilet. On my return journey I went via the kitchen and had a couple of Panadols.

Back in bed I made a distinct whimpering sound. Immediately, right on cue, John started stroking my head. Ten seconds later his breathing pattern indicated he was sound asleep again, as did the fact that his hand had become a dead weight on top of my face and I had to lift it off in order to breathe.

And so I lay there.

Worrying.

About everything.

I worried about John having an affair and falling in love and possibly even leaving me and having a baby with Ruth, one of his work colleagues. I mean, why wouldn’t he? She was hot and, what was more, clearly loved the way he played his ukulele (and no, that isn’t a euphemism). And hadn’t she only a week earlier told John she loved his wild, silver hair? In fact, hadn’t she told him he looked like Richard Gere? That was the same day I’d told John he looked mental and needed a haircut.

I worried about our kids. Of course I did. I had good reason. Our twenty-three-year-old-daughter, Bonnie, was a video installation artist! For God’s sake, what the hell was a video installation artist? I didn’t have a clue. All I did know was that she and her boyfriend had recently moved to Berlin, where they were surviving on a sack of potatoes and wine that cost fifty cents a litre. The day before departure she’d announced to John and me: ‘You guys do understand what’s going on here, don’t you? I’m not just going travelling, you know. I’m going to Berlin to live. I might be gone forever.’ Since I’d seen how much, or rather how little, Bonnie had in her bank account, I considered that highly unlikely.

But on the night before I went away on tour I was extremely focussed on one specific worry—namely that Bonnie had been murdered in a forest somewhere in Portugal. It wasn’t out of the question; after all, at that moment in time she was in Portugal, and as far as I knew (although geography has never been my strong suit) they had forests there, and what’s more, she was participating in a visual arts workshop run by a philosopher who wore a black skivvy! I may have made up the black skivvy bit, but whatever. He was a philosopher running a visual arts workshop! What mother wouldn’t be having an anxiety attack? Bonnie had met him at a dinner party in Berlin. Apparently he was ‘amazing,’ and had offered her the workshop for free, assuring her he’d also find somewhere for her to sleep. I bet he will, was my immediate thought. Oh why did we ever lend her the money for the airfare? What idiots we’d been. Oh God. Oh please, please, please let her be okay. If only I could ring her. But that was out of the question because, as usual, she had no phone credit.

I worried about my twenty-five-year-old son, Jordie, being a drug addict. Why wouldn’t he be? He was a musician! And there was that ex-girlfriend who’d posted on YouTube that song she’d written about him snorting coke for breakfast, morning tea, lunch, afternoon tea and dinner. According to her he even sprinkled it on his cornflakes! I’d got quite a shock when I first saw it. But my son had assured me, ‘Mum, she’s exaggerating.’ And, when I thought about it, that was more than likely true. For starters, he didn’t eat cornflakes, never had: he was allergic to milk.

I worried about why, at the age of fifty-four, I was continuing to torture myself in a quest to become a good stand-up comedian. It was a young person’s game. I was at best mediocre, and nothing annoyed me more than a mediocre comic with half-arsed commitment. Oh God, the thought of walking out onstage and banging on about getting older, being a mum, being overweight, blah, blah, blah—it made me feel sick. It brought me no joy. I felt entirely shithouse about it. So why not quit comedy? Yes! That was what I’d do. At the end of the tour I’d quit comedy for good.

* * *

Insomnia makes you think crazy thoughts. And the worst part is that they go on and on and on because the night goes on and on and on.

At one point my chest tightened and I wondered if it was a heart attack. What if this was it? What if I died? At least I wouldn’t have to go away on tour.

I closed my eyes and tried the old counting-sheep routine but became distracted wondering where the sheep went after they jumped over the stile; when they left my head, where did they go? Did they gambol and frolic in a nearby field or …? And that was when I saw a neon sign blinking the word ‘abbatoir’. Not that I’m a vegetarian—I love a chop as much as the next person—but it was upsetting to realise that in the process of helping me get to sleep those innocent lambs were being sent to their deaths. But then again maybe it was just the same three sheep going around and around?

I sighed.

And, would you believe it, a couple of seconds later John woke up and said, ‘What’s the matter, Scotty?’

I find that sort of thing totally amazing. I guess it’s what comes from being with someone for thirty years. All I’d had to do was sigh …

And then sigh again …

And again … making each sigh louder and more distressed until I was sort of crying, and then I started to toss and turn quite ferociously, throwing the doona off and on, at one point pausing to hurl the ‘stupid fat fucking European pillow’ across the room. ‘Why do they exist? You can’t sleep on them. And oh, that fucking streetlight.’

I actually said the words aloud. But the light was shining right into my face. Wasn’t that why we’d had holland blinds custom-made in the first place—to stop the streetlight coming in? And what had happened? The blind man came, took the measurements, went away, made the blinds, came back, installed them, and that first night I was forced to wonder if the blind man wasn’t indeed just that—blind as a bat—because the new blinds were too narrow and the light was still pouring in. And what did we do about it? Nothing. Absolutely nothing. Sure, John did ring the blind man the next morning and leave a message saying there was a problem and could he ring back asap, but that was sixteen years ago and we were still waiting for him to call.

And then, after moaning about the light, I leant over and whispered in John’s ear, ‘John? John? John, are you awake?’

And then with my index finger and thumb I got a teeny tiny bit of skin on his back and gently twisted it.

And then I sighed again.

And then, incredibly, John just woke up … intuitively.

‘What’s the matter, Scotty?’

‘I can’t sleep.’

‘Come here.’

I shuffled backwards towards John and we lay spooning, one question mark inside another.

‘Geez, you’ve got a great arse, Scotty.’

‘Oh John …’

‘You have. You’ve got a really great arse.’

‘Yeah, okay, I’ve got a great arse. Whatever. I just wish I could sleep.’

‘I know something that will help you to sleep.’

‘Oh no, John, not now.’

It has to be said that John is the most optimistic human being I have ever met. In the most hopeless of circumstances he never gives up.

‘I’ll tell you a dirty story.’

‘John, please, no.’

And away he went. ‘Okay, I’m home alone in bed when suddenly I wake up and I see a woman. It’s you, Scotty.’

‘Good call, John.’

‘You walk into my room. You’re wearing a see-through dress and you’ve got nothing on underneath.’

‘I’ve changed my mind. I don’t want to be in your story. I don’t want to be naked in a see-through dress.’

‘Why not?’

‘Because these days I can’t get away without at least wearing a bra and underpants.’

‘But Scotty, you look beautiful.’

‘In your head I look beautiful, but in my head I look disgusting, so please get me out of your story.’

‘Well, okay then, I’m in bed and this beautiful woman with long dark hair walks in.’

‘Long dark hair? Are you talking about Ruth?’

‘Who the hell is Ruth?’

‘Who the hell is Ruth? You know exactly who Ruth is.’

‘I don’t, Scotty.’

‘Ruth is that spunky woman at your work who said you look like Richard Gere.’

‘Oh, for God’s sake.’

‘Well, she’s got long dark hair and she’d look hot in the nude.’

‘I’m not talking about Ruth. I’ll start again, okay? Alright. I’m in bed and this woman with short red hair …’

‘Julia Gillard?’

‘Oh, Scotty …’

‘I don’t mind if it is. For some reason I don’t find that situation threatening.’

‘Let’s forget about hair. A woman walks into my bedroom. She’s wearing a see-through dress. Slowly she unbuttons it and it slips to the floor. She gets into bed and curls around me. I feel two hard things pressing into my back. They feel like macadamia nuts.’

‘Macadamia nuts?’

‘Her nipples …’

‘She’s got nipples like macadamia nuts?’

The Tour

The Tour